By almost all accounts, Albuquerque, New Mexico, music instructor Nick Prior is an all-star teacher. He runs six choirs, which serve nearly 200 students at the city’s Eisenhower Middle School. His choirs have won state competitions three times, and in multiple categories. Last year, his students swept a national choir competition, earning first place in showmanship and musicianship. He won a statewide award for teaching from the New Mexico Music Educators Association in 2014.

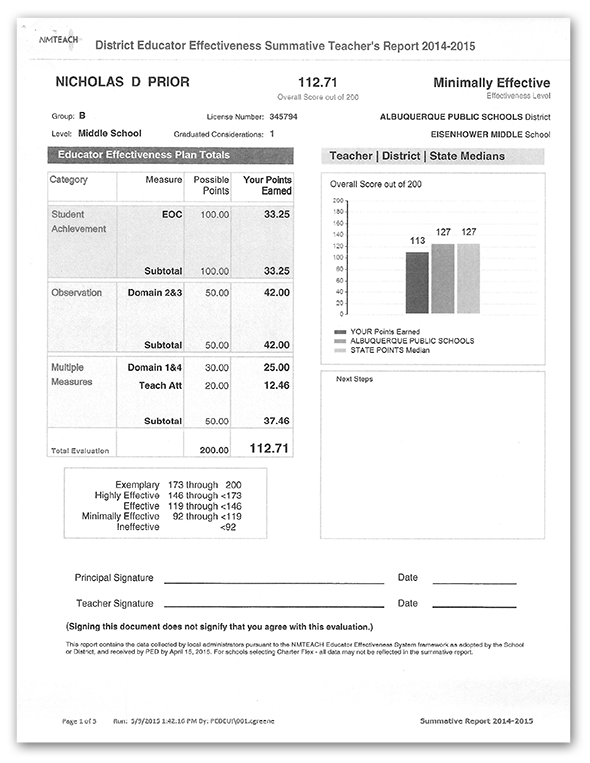

But earlier this year, when Prior received his teacher evaluation, he was deemed “minimally effective”—earning just 33.25 points out of a possible 100 in the “student achievement” category that made up half of the document.

The reason? The “student achievement” had nothing to do with music. It was based on the state standardized test scores in reading and math of the lowest performing quarter of students in his school. Many of those students had never taken one of his classes. The other half of Prior’s rating was based on a combination of classroom observations, teacher attendance, and student and parent surveys. He scored at or above average in these areas, but not high enough to counterbalance the low student achievement rating.

Prior’s dilemma has become increasingly common. Forty-two states across the country have moved in recent years to evaluate all teachers at least in part on student test score growth, according to the National Center for Teacher Quality. But tens of thousands of teachers work with students in grades that aren’t tested (like kindergarten) or subjects in which standardized tests typically don’t exist (like art, music, and physical education).

While no official count of states or districts exists, teachers in a handful of places have been or will be judged partially based on test score results for grades or subjects they don’t teach, including in Florida, Nevada, New Mexico, and Tennessee. Officials in Nevada are even considering how they might hold support staff—like school nurses and counselors—responsible for student test results, arguing that they impact student achievement by keeping students healthy and able to learn.

The move has, predictably, drawn howls from teachers and their unions—and prompted lawsuits. In some places, it could be the final straw that discredits the whole attempt to evaluate teachers on student test scores. The debate also speaks to the ongoing tension over the changing roles of teachers in an age of heightened accountability: Are educators narrow-subject-area specialists (possibly necessitating the creation of new tests in everything from music to PE)? Or are they generalists who should all be held responsible for teaching foundational skills such as literacy and math? The experience so far suggests that the answer lies somewhere in the middle, and what matters most might be how well school leaders help teachers adjust to new evaluations, regardless of how they are designed.

* * *

The places that grade specialty-area teachers based on reading and math results vary widely in their approach.

In Chicago, for instance, schoolwide scores from language arts and math tests count for 10 percent of elementary and middle school teachers’ evaluations in subjects like social studies, science, fine arts, and PE. (For high school teachers, it’s 5 percent.)

Elsewhere, though, the proportion is much larger. This year in Tennessee, it was 25 percent.

In Florida, it can be as high as 40 percent. And in New Mexico, it’s 50 percent; districts there can decide how to calculate student test data for teachers in untested grades and subjects, often opting to use schoolwide averages.

Teacher evaluations are typically based on a combination of classroom observations; various measures of “professionalism,” such as attendance and taking advantage of professional development opportunities; and student achievement, which can be measured in different ways. This calculus often impacts eligibility for things like tenure and pay bonuses.

Prior, for instance, makes just $30,000 per year and had hoped to advance from a “level one,” or beginning, teacher to a more advanced level that would bump up his salary to $40,000 in the upcoming school year. But his recent low rating disqualified him. If Prior’s score doesn’t improve next year, he could lose his teaching license.

Nick Prior’s teacher evaluation form. Courtesy of Prior.

In recent years, the experience of teachers like Prior has proven to be a weakness in the push for more data-based teacher evaluations—an at-times absurd wrinkle that critics of the new approach never hesitate to point out.

Morgan Polikoff, an assistant professor of education at the University of Southern California who has studied teacher accountability policies, likens it to holding employees responsible for a task they weren’t hired to perform—like grading an obstetrician based on how many successful heart surgeries her hospital completes. “Pretty much anyone would say they wouldn’t want to be evaluated that way,” he said. “The fact that is it so obviously [unfair] sort of undermines the whole enterprise.”

Teachers unions have hardly been blind to this fact, challenging the practice in the courts. The latest lawsuit was filed in February by the Tennessee Education Association, an affiliate of the National Education Association, the country’s largest teachers union. (The NEA also backed the suit.). It’s the third lawsuit targeting the state’s teacher evaluation plan. None of them have been resolved.

Under the current plan, Tennessee teachers who don’t have test data in their grades or subjects are evaluated using schoolwide test scores taken from state standardized tests. Those scores count toward 25 percent of their total evaluation (though a recent bill will lower that amount to 15 percent over the next two years). The union argues this violates teachers’ rights.

The lawsuit names Theresa Wagner, a physical education teacher at Gra-Mar Middle School in Nashville, Tennessee, who was denied a bonus last year because of low schoolwide test scores. The suit also names Jennifer Braeuner, a visual arts teacher at Norris Middle School in Anderson County, just north of Knoxville, who was denied tenure for the same reason.

Wagner declined to comment on the suit, and Braeuner could not be reached. But Erin Davidson, a first-grade teacher at Raineshaven Elementary School in Memphis, says it’s unfair to judge teachers based on the scores of students they don’t even know. Because state testing doesn’t begin until third grade in Tennessee, part of her evaluation is based on the performance of students who may never have set foot in her classroom.

“Now you’re going to say that I’m not effective because I didn’t teach them?” says Davidson.

Beyond identifying ineffective teachers, evaluations are intended to help teachers improve. But Davidson says other students’ data gives her no information about how she might change her teaching practice to better help her students.

In Florida, where the state’s department of education currently allows districts to determine how best to calculate the test score portion of evaluations, educators also sued over grading teachers based on subjects they don’t teach. The test scores are worth at least 40 percent of teacher evaluations in some districts. In 2014, a judge agreed that the method was deeply unfair but ruled against the teachers, saying that it was not illegal. The teachers filed an appeal that is currently pending.

* * *

While some states are holding PE, art, and music teachers responsible for math and reading results, others are developing new, subject-specific tests for subjects that previously went untested.

Photo illustration by Juliana Jiménez. Photo by Thinkstock.

The problem is that many states and districts have rushed the execution of both strategies: Teachers in traditionally untested subjects say that if they’re to be held responsible for foundational skills in which they’re not licensed, they need better and more widely available training in them. And new subject-area tests in areas like music and art must be thoughtfully designed to provide meaningful feedback on teacher performance. Polikoff says these tests vary considerably in quality.

The New Mexico Public Education Department is phasing in end-of-course exams for subjects not covered by the state test, including a music test. But when these specialized exams aren’t used, districts are allowed to determine an alternative way to calculate the student achievement portion of evaluations for teachers. Among their options is the choice to use schoolwide state test averages from a group of kids known as “Q1 students”: the lowest performing quarter in the school. Albuquerque Public Schools, where Prior works, chose this method.

In Chicago, district officials are trying a hybrid approach: Specialty-area teachers get evaluated on both schoolwide standardized test scores and on new tests created by groups of teachers.

A high school music exam, for example, requires students to sing scales (grading them on pitch and accuracy) and to also sight-read a piece of music. The short music test takes about five minutes to complete. Results count for 25 percent of high school teachers’ evaluations—significantly more than the schoolwide test scores.

Casey Fuess, a high school music teacher at Lindblom Math and Science Academy, gave the music exam to his beginner’s orchestra, band, and choir students this year. He said the short test, while better than some multiple-choice exams, doesn’t provide him with any new information about his students’ progress. He would prefer a test that more substantially probes students’ music literacy.

Yet Fuess prefers this test to basing his evaluation on schoolwide reading or math test scores—a practice he calls “offensive.”

“It makes me question the purpose of the evaluation system,” Fuess says.

Indeed, if all teachers are going to be held responsible for results in core subjects, Chicago teachers say they will need more consistent professional development to help them teach skills they were never trained or licensed to teach.

“I’d be a lot more open to it if all teachers were properly trained,” said George Mueller, a veteran social studies teacher at Dunbar Vocational Career Academy, a public high school on Chicago’s South Side. Mueller said the district offers some general training for all teachers in reading strategies, but bad winter weather this year canceled some sessions. “We’re not getting the constant training that I think would be beneficial,” he says.

In the meantime, some teachers have taken matters into their own hands, collaborating with other educators to find ways to teach foundational skills across different subjects.

In one example, Micah Miner, the social studies department head at Nancy B. Jefferson Alternative High School in Chicago, says he worked with the English department to figure out which literacy skills could be addressed in both social studies and English classes—including reading strategies that help with comprehension.

Experts agree that the onus shouldn’t be solely on teachers to prepare for the new evaluations. But as states fumble through policy changes that are very much trial and error, teachers and their students could ultimately pay the price.

In Albuquerque, Prior has only taught for four years, but already he is convinced that there is no other job for him. The drama surrounding teacher evaluations, while frustrating, won’t push him out of the profession. If someday he is unable to teach in New Mexico because of a negative evaluation, he will simply find a teaching position elsewhere, he says.

Prior is 26 and has no family commitments, so the move would be an easy one. But he fears the same isn’t true for many of his colleagues.

“It’s incredibly disheartening,” Prior says. “They’re going to push away a teacher who could be brilliant.”