Opinion: Here’s how my students have shared their anger and pain about systematic racism and oppression

Riehman teaches social science at El Cajon Valley High School in El Cajon. She is a 2020-2021 Teach Plus California Policy Fellow, and lives in South Park.

In 2016, when I was in my first year of teaching, a former Ugandan refugee named Alfred Olango was shot and killed by police officers on my town’s main street. He had been walking with his sister when she noticed that he “wasn’t acting like himself,” and she called the police for help. After El Cajon police officers arrived, they tasered and shot Alfred Olango several times. What they thought was a weapon turned out to be an e-cigarette. Our city erupted in protest, often turning violent.

Three blocks away, our high school went into secure campus protocol. Quickly, the news of the shooting spread like wildfire. My students were all too familiar with the rise of police brutality and we had recently studied what would soon become known as the Kaepernick effect when we discussed racial disparities, civic duty and our personal responsibility to act.

We provide this platform for community commentary free of charge. Thank you to all the Union-Tribune subscribers whose support makes our journalism possible. If you are not a subscriber, please consider becoming one today.

That day, I could feel the student’s frustration, anger and pain. Many of them joined community protests after school, and we also encouraged them to protest in other ways. Students set up a “Day of Silence” and held a lunch assembly where they spoke from their heart. Some of my students also stayed seated during the morning’s Pledge of Allegiance. That decision caused considerable controversy in my school.

To address it, I set up a debate giving my students an opportunity to express their views. Tears flowed on both sides, as they shared their personal pain with one another.

One cried in frustration as he described the three years he spent in a refugee camp trying to get to the U.S. through legal means. He was grateful that he and his family escaped Iraq before the Islamic State had dismantled their village.

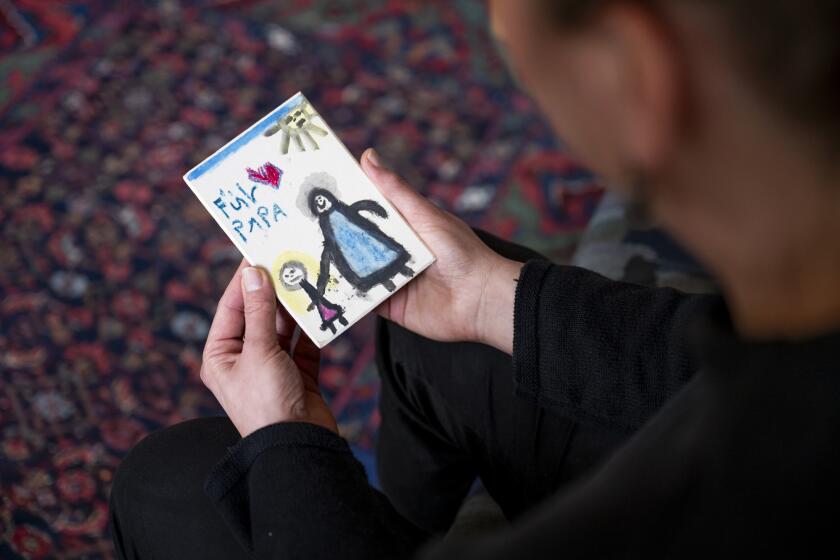

Another broke out in tears because her father had been taken into custody by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement while she was at school. “How can I stand for a country that doesn’t care about me?” she said.

This experience changed me in profound ways.

Today more than ever, my students need opportunities to think through their feelings, apply their knowledge, and share their experiences. Systemic oppression, food insecurity and the isolation they’ve experienced because of the pandemic are just some of the issues that have affected my students deeply.

I have learned to really listen to my students. Listen to not just what they say verbally, but also what they say in their movement, level of engagement, body language and tone. My students have a lot to say even when they are not speaking, and we have a responsibility to listen.

Recently, I adapted a lesson from “Teaching Tolerance” called “Countering Islamophobia.” In this lesson, we looked at the experiences of people stereotyped based on their religion, race and gender. When discussing these scenarios, my students began to tell their own stories of feeling marginalized, belittled and stereotyped. I then invited them to create an ad campaign that identified a specific stereotype, discuss how the stereotype may affect how one sees their identity, and demonstrate how they could change peoples’ perspectives.

The results were amazing. Their campaigns illustrated various racial, religious and gender stereotypes from their perspective.

One student’s ad campaign, titled “Asians Aren’t Viruses,” highlighted recent discrimination against Asian Americans. She wrote, “We must respect their culture and not point fingers when it’s a global pandemic affecting everyone.”

Another student wrote about an ad campaign addressing stereotypes about young Black men, “These stereotypes affect us because now people have this preconceived notion that being Black means something dangerous and that leads to innocent people being persecuted or even dying.” In his campaign, he showed images of young Black men in handcuffs.

Especially in this moment, we have an opportunity to reimagine what school looks like this spring, this summer, and into next year beyond just addressing the lost instructional time and COVID-19 trauma. We have a chance to really listen to our students, to leverage their strengths and insights, to look at them as partners in creating learning experiences. To start, we have to meet our students where they are.

I often think about the group of students from 2016. Their passion and voice continue to inspire my work as an educator. My students have shown me that they want to be a part of the learning process when they are affirmed and respected. Our students have incredible power, and it is up to us to facilitate the kinds of learning experiences that inspire them to take that power and use it to elevate their voice.

Get Weekend Opinion on Sundays and Reader Opinion on Mondays

Editorials, commentary and more delivered Sunday morning, and Reader Reaction on Mondays.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.