As the daughter of a former librarian, Anna Mayotte has long been passionate about literacy. So a job teaching kids to love reading was a natural fit.

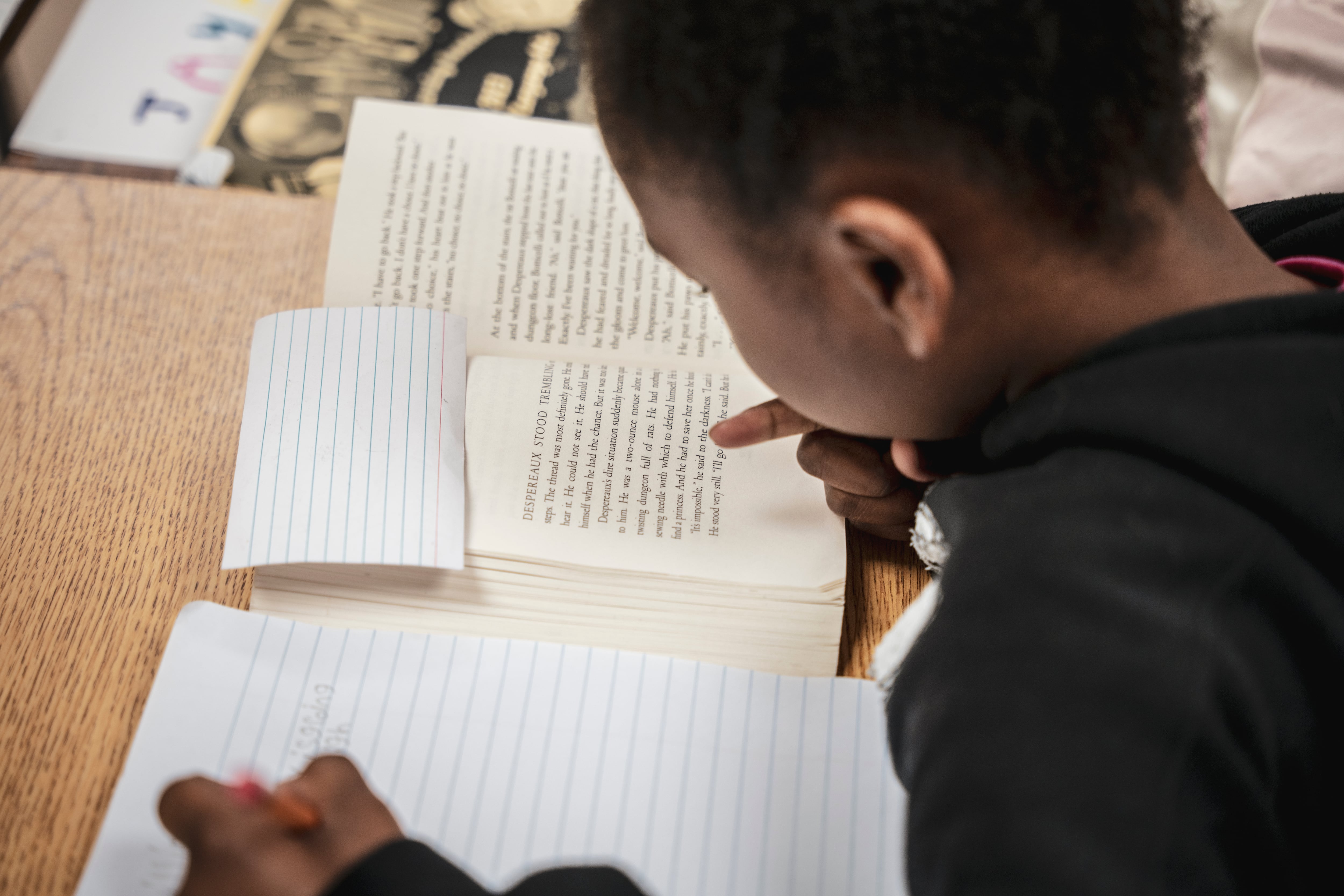

As a fifth grade English language arts and social studies teacher at Gardner Elementary School in the Detroit Public Schools Community District, Mayotte improves literacy skills in her classroom by meeting with students in small breakout groups for part of the day. She gets them excited about the books they study by reading aloud in a theatrical, exaggerated manner. She also makes sure to keep her classroom library stocked and connect kids with the kinds of stories they enjoy reading and reflect their own identities. Mayotte engages her students in the literature they explore by connecting the pages to their lived experiences.

When the class reads “Esperanza Rising,” by Pam Muñoz Ryan, for example, her students learn about the racism poor immigrant farm workers faced after World War II. The kids then discuss the racism they have experienced in their own communities, as Gardner Elementary serves a predominantly Black student body. They talk about the threats to basic human rights described in the literature and the parallels they see playing out around the world today.

“Before we begin the book, I ask them why they think it’s important to study human rights,” Mayotte said. “I always go back to the fact that if we don’t know what our rights are, we don’t know when they are being violated and when to stand up for ourselves.”

(Books like “Esperanza Rising” have been challenged in school libraries and curriculum for years, with conservative lawmakers arguing that texts dealing with race and racism aren’t appropriate for young readers).

Mayotte, recently selected for the Education Trust-Midwest Michigan Teacher Leadership Collaborative, said reading literature that covers those topics gets students thinking and “practicing that muscle of empathy.”

“I absolutely think it’s beneficial and I would say it’s necessary because these things are happening to kids in all age groups,” she said. “If it’s happening to them, it’s something we should be talking about.”

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

There wasn’t one specific moment. I am one of those teachers who has always known they want to teach. From a young age, I’ve had a love for learning and children and knew I wanted to make a difference in the lives of students. Growing up, school was my home away from home and some of my favorite memories from childhood happened within the school building. It’s where I made lifelong friends, and the experiences I had in school shaped me into who I am today.

How do you get to know your students?

I try to find out little things about them like what they enjoy doing in their free time. But the best relationship building comes from the casual conversations we have while eating breakfast together, in the hallway, or at dismissal. Many of our students are newcomers to the country, so I also try to get to know their home culture and learn some words in their native language to connect with them. Students appreciate when you take the time to make those connections and even though they may seem small, they can make a huge difference in how welcome a student feels at school.

Tell us about a favorite lesson to teach. Where did the idea come from?

While I can’t take credit for it, our first English language arts module of fifth grade is my favorite. While reading “Esperanza Rising,” we make connections to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We talk about what human rights are and how this document was written post-World War II. Even though the writers of this declaration set out to ensure that those atrocities never happened again, we discuss how people still have their rights threatened today. Students find examples of human rights being defied in the novel and then write to raise awareness about how people are still experiencing this hardship in today’s world. My students absolutely love the book, and I love seeing them practice empathy while also working toward the goal of becoming proficient writers.

What object would you be helpless without during the school day?

I’d be helpless without my wireless slideshow clicker. I’m constantly moving throughout my classroom to check for understanding during a lesson, so I use the laser on the end to draw students’ focus to different anchor charts or a specific part of the text that we’re reading. It allows me to keep the lesson moving without having to stand in one spot.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your class?

The lasting impacts of COVID on our community and classroom cannot be understated. Many of our students and families are still dealing with the trauma of the pandemic and that’s resulted in a mental health crisis. We also have students entering fifth grade without essential foundational skills from previous grades. I have to be a lot more strategic in my instruction to make sure all my students are learning at grade level and get the interventions they need. There’s a huge push to bolster research-backed literacy instruction in the early grades, especially coming out of the pandemic. I am part of the 2023-2024 Education Trust-Midwest and Teach Plus Michigan Teacher Leadership Collaborative, which empowers educators to advocate for policy changes that will positively impact students. One of the things my colleagues and I are advocating for is ensuring that training in early reading intervention is provided to all Michigan educators to help close this gap made worse by the pandemic.

Tell us about a memorable time — good or bad — when contact with a student’s family changed your perspective or approach.

During the pandemic, we conducted daily wellness checks on our students and families. These very quickly transitioned from just checking in to see how everyone was doing to hearing about illness, loss, and food and housing insecurities and then trying to locate resources to help. It reminded me that being an educator and part of a school community is so much more than just what happens inside the classroom, and for many of our families our schools are a lifeline. We offer wraparound services and resources on which so many in our community depend. It kind of expanded my perspective from just thinking about the students that I serve to include the families and the community.

What part of your job is most difficult?

I think the most challenging part of teaching is meeting all the individual needs of my students. I have many students and they all come to school with different academic, behavioral, and social-emotional needs. I plan individualized instruction and after teaching the whole group, I meet with students in small groups to teach the skills in which they need more practice. Sometimes I use this time to just talk with students about how things are going and provide emotional support. Students thrive during these moments, and I’ve seen a lot of students make progress. Unfortunately, meeting every single student’s needs is impossible and even though I try to do everything I can to make sure they are getting what they need from me, it can be overwhelming and disheartening when those needs are not met.

What was your biggest misconception that you initially brought to teaching?

When I came into teaching I believed that I was going to be able to make big changes to the education system. I didn’t have a full understanding of how the system worked nor did I understand just how many stakeholders there are in the world of education. There are so many people who are situated within a school or district, all working toward the same end goal of student success, but in different ways. It can be really hard to navigate that within the classroom, but I work hard to advocate for my students and the changes that I know will have a positive impact on their lives.

Recommend a book that has helped you be a better teacher, and why.

“The Reading Comprehension Blueprint: Helping Students Make Meaning from Text” by Nancy Lewis Hennessy has really changed my perspective on reading instruction. It translates the research on each dimension of skilled reading into useful practice. So much of the literature on the science of reading focuses on word recognition, which is helpful. But for the upper grades, a lot of our focus is on reading comprehension. This book discusses how to align comprehension instruction with that same science of reading research. One of the most helpful things about this book was that it shifted my thinking of comprehension taking place at the text level to how understanding at the sentence level is how students derive meaning from the whole text.

What’s the best advice you’ve received about teaching?

Prioritize your responsibilities. Teachers have so many things on their plate and there’s no way to get everything done. Take a look at your to-do list and identify what items will have the biggest impact in your classroom. For me, that’s carefully planning out instruction and providing meaningful feedback on student work. My advice: complete those tasks and then leave work at work. Rest and enjoy your family at home so you can show up for your students the next day.

Hannah Dellinger is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering K-12 education. Contact Hannah at hdellinger@chalkbeat.org.